Yuri Monogatari 5

Yuri Monogatari 5

Edited by Erica Friedman

Rated MC, 18+

ALC Publishing, $15.95

This most recent volume of the pioneering lesbian manga anthology is 4 cents cheaper than the previous volume, 50 pages longer, and 100% better.

All the Yuri Monogatari anthologies are labors of love, and they serve an important purpose: Providing readers with true lesbian manga. But noble intentions don’t necessarily make for good comics, and while some of the pieces in Yuri Monogatari 4 were stellar, others weren’t quite ready for prime time.

Not so with volume 5. The stories still vary in style and tone, but overall the bar has been raised. As I commented in my original review, much of the art in YM4 was over-drawn and tried to use style and flourishes to cover deficiencies in anatomy and form. That’s not a problem in volume 5. The non-Japanese comics in particular are drawn with a simplicity and vigor that suggests the creators are getting more confident in their work.

That feeling is reinforced by the overall optimistic tone of the stories. Each one presents a dilemma that is resolved, usually resulting in a happy ending and lots of joyful sex. (The exception is Niki Smith’s “Your Hair,” which chronicles the waning of a relationship in a series of quiet, sad vignettes.) In Sakuraike Taki’s “Last Day,” two schoolgirls resolve to commit suicide together because their parents want to keep them apart. With spare and sketchy drawings, Taki shows how one type of defiance begets another.

Sirk Tani’s “Love Won” also deals with the problem of intolerance, but in a more idealized way. She tells her story of a teenager’s angst about being outed as a series of nested dreams, with an ending that is a bit too pat but characters who are breezy and likeable.

Jessie B.’s “Vagrants,” on the other hand, is pure fun, a hilarious whirlwind tour of all the bad jobs in the world, rendered in an energetic, thick-lined style. As with most of the non-Japanese stories, this looks more like indy comics than manga, but it’s pretty likeable anyway.

One artist who has shown impressive growth between volumes 4 and 5 is Althea Keaton, who contributed “Cog” to vol. 4 and “Umbrella” to vol. 5. Her line is more confident, her figures more solid, and her writing more convincing, in this latter story.

Once again, the Japanese stories are excellent. “Until the Sun Sets, Then Rises Again” is quiet story of a woman dealing with her insecurity about dating a much younger woman. The art is lovely but difficult to fully appreciate as the comic has obviously been shrunk from a much larger size. And while another dose of Rica Takashima’s cheerful and super-cute “Rica ‘tte Kanji?” is always welcome, she’s getting stiff competition from Sakuraike Kana, whose “On the Road Where the White Flowers Bloom” is a humorous tale of two yuri doujinshi creators, only one of whom is a lesbian.

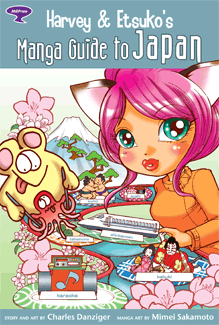

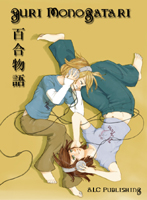

Even the cover of this volume is different. Kristina Kolhi has replaced the shadowy silhouettes and severe single-color scheme of the earlier volumes with a full-color, nicely rounded drawing of two girls sprawled together listening to music. It accurately reflects the tone of the book: girls having fun with girls.

“Better” is not the same as “perfect.” This volume has its share of stiff figures and awkward anatomy, but the artists all share a confident style and a cheerful, comfortable outlook that go a long way toward making this an enjoyable read despite the occasional flaw.

This review is based on a complimentary copy provided by the publisher.