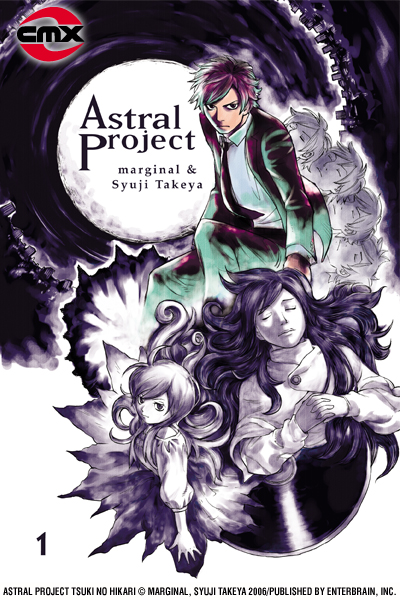

Astral Project, vol. 1

Astral Project, vol. 1

Written by marginal (Garon Tsuchiya)

Art by Syuji Takeya

Rated M, Mature

CMX, $12.99

Astral Project is a smartly drawn supernatural tale set in the grittier parts of modern-day Japan. If this first volume is any indication, it’s more of a mystery than a horror story; it just happens that the ability to leave one’s body and float off into the night sky is an important plot element.

Masahiko is your typical alienated young man of fiction, estranged from his parents, living alone in a small apartment, working nights as a chauffeur for a high-end call girl service. As the story opens, he gets a call from a total stranger telling him that his sister, Asami, has died. He goes home for her funeral, dodging his father, and takes back with him only one thing to remember her by, the CD she was listening to when she died. But when Masahiko listens to the music, something startling happens: His soul departs his body and goes floating over the streets of Tokyo.

At first, he thinks that this is what killed his sister—she left her body and couldn’t get back in time. This story is far more complex than that, however, and the creators unspool a number of plot threads in this first volume. Masahiko takes the CD to a jazz expert who identifies the musician performing the music, but this session is like none other ever recorded. There are hints of plots and conspiracies. Yukari, Asami’s friend who broke the news to Masahiko, pursues him, but he’s not interested; all he wants to do is figure out what happened to his sister. Tantalizing clues are dropped along the way.

As that plot develops, Masahiko is also testing out his newfound power to leave his body behind and travel around Japan. He starts to meet others who have similarly shed their skin: Zanpano, an old man who is a wino on earth but more of a wise elder in the astral plane, and a mysterious, gruff young woman.

Although Astral Project tries to be dark, there is an element of innocence to the story. Masahiko works with call girls, but his one friendship with a co-worker is strictly platonic. What’s more, he is drawn not to the alluring Yukari but to the younger, more innocent girl he meets on the astral plane. This, plus his resentment towards his parents and his boyish love of his big sister, make him seem very young. Aside from the scantily clad call girls, there isn’t much in volume 1 to merit an M rating; perhaps, as often happens, the sex and violence will be ramped up in later volumes.

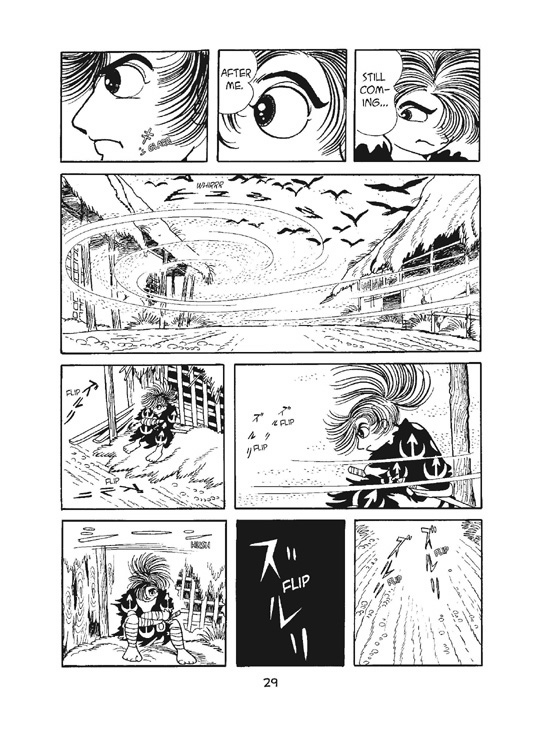

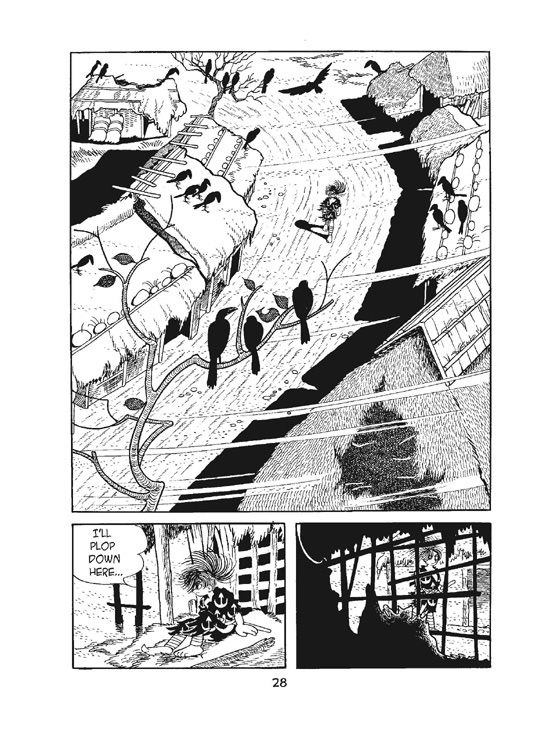

Takeya’s art is intriguing but rather odd; the faces and figures may seem stiff and out of proportion, and the backgrounds seem to have been designed by M.C. Escher, but the overall effect is slick and expressive. Takeya likes to pull in tight on characters’ faces, particularly at moments of revelation or emotion, and he composes the page in interesting ways, often just showing slices of faces and objects to unfurl the story. In most of the book he uses just two or three tones, which gives his figures an almost metallic smoothness. This would be monotonous in lesser hands, but Takeya is not afraid to experiment with hatching and stippling to add interest. The only place this doesn’t work is in Chapter 3, when he starts rendering Masahiko in a rougher, scratchier style. It doesn’t work very well, and he soon reverts to his smoother, more linear technique.

The characters are one of the best parts of this book. Tsuchiya’s writing and Takeya’s character designs produce a cast of unique characters, each one different and interesting in his or her own way: Masahiko’s plump call-girl friend, the ponytailed jazz expert, the crafty Zanpano. Admittedly, the main characters are manga stereotypes—the blank-faced, slightly bitter young man, the seductress, and the innocent young girl, but the rest of the cast is a rich and varied crew.

There are no extras, but the slightly larger trim size of this volume shows off the art to good effect, and at least partly justifies the higher price tag. Takeya’s art has a monumental quality—he often fills a panel with a single image of a head or a hand—and his nightscapes are breathtaking. It would be a shame to squeeze those down to standard tankoubon size.

This first volume sets up a supernatural mystery with an interesting puzzle, some intriguing characters, and a polished, occasionally edgy art style. I’m looking forward to seeing where the creators bring it from here.

(This review is based on a complimentary copy supplied by the publisher.)