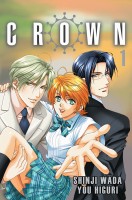

Crown, vols. 1 and 2

Crown, vols. 1 and 2

Written by Shinji Wada

Art by You Higuri

Rated OT, for Older Teens (16+)

Go! Comi, $10.99

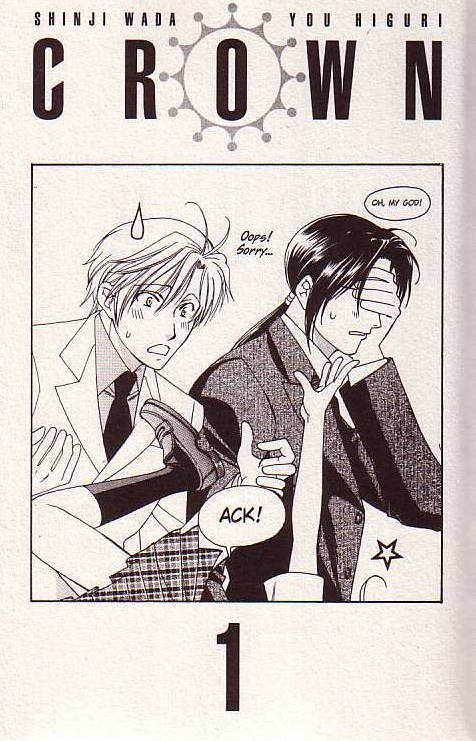

When I first looked at the cover of the first volume of Crown, my heart sank a bit. Could you get any more cliched than that—two hot guys with a girl in the center? Then I turned to the title page…

… and I literally laughed out loud.

And that’s Crown. Written by veteran shoujo manga-ka Shinji Wada and illustrated by the superbly talented You Higuri, Crown is an enjoyable spoof of the many clichés of shoujo manga. It starts out with a girl who is so sweet that the book should come with its own insulin pump. Mahiro is left alone when her mother dies and an evil family kicks her out of her house, but she works two jobs so as not to be a burden on anyone. She is at her night job, as a flagger at a construction site, when two guys scoop her up, toss her into a limo, and drive away.

They are not kidnappers, however, but hardened mercenaries from another country, and the blond one is Mahiro’s older brother, Ren. It seems that Mahiro and Ren are actually a prince and princess, but their evil stepmother conspired to have them killed so she could inherit the throne. They were just spirited away instead, and the queen has just learned that Mahiro is still alive. She wants to assassinate Mahiro, but Ren has sworn to protect her; his partner Jake is along for the ride because of a poker debt, but also, we eventually learn, to fill a greater emotional need.

There is plenty of action in this story but it’s all tongue in cheek. Ren and Jake are super-mercenaries, the best in the business. They dispatch the evil family who took over Mahiro’s house, then take her out to dinner even as the queen’s mercenaries are surrounding the building; they follow up their gourmet meal by blowing up an entire section of Tokyo. And they leave bodies scattered everywhere. Soon another mercenary gets dragged in: The Condor, who is fired ignominiously after he fails to capture Mahiro and ends up being so captivated by her sweetness that Ren and Jake hire him as her protector. Oh, and there’s a cross-dressing assassin, too, but I don’t want to give too much away.

Wada and Higuri have a lot of fun with the clichés of manga. Ren and Jake are impossibly good at what they do, calculating their opponents’ moves to the split second. They wear full camouflage uniforms under their impeccably tailored suits, and they are fond of striking the sorts of poses you usually see on movie posters. Also, they shower together and generally act like seme and uke, except there is no sexual tension (or sex) between them. Mahiro, for her part, is so cute and naïve and generally obliging that by the second volume Higuri has started to draw her with puppy ears and a wagging tail. She fixes elaborate breakfasts, cheerily greets Ren’s one-night stands, and drags Condor off on a shopping spree. She and Ren also display an unnatural amount of affection for one another. All the characters act out stereotyped manga roles, but they are completely clueless about it; it’s as if Wada and Higuri are winking at us over their heads.

Since both creators are old hands, it’s no surprise that this manga is very well done. Higuri’s art is outstanding, although Mahiro’s moe-ness gets to be a bit much after a while. Her attraction to Ren is a bit icky, but it’s played as mostly unconscious and hopefully it will be resolved in the usual way (“What? You’re adopted?”) in vol. 3. (It’s hard to believe they could resist that cliche, having included most of the others.) The story is entertaining and completely over the top, but if you’re willing to suspend disbelief, it’s an enjoyable ride.

(This review is based on complimentary copies provided by the publisher.)