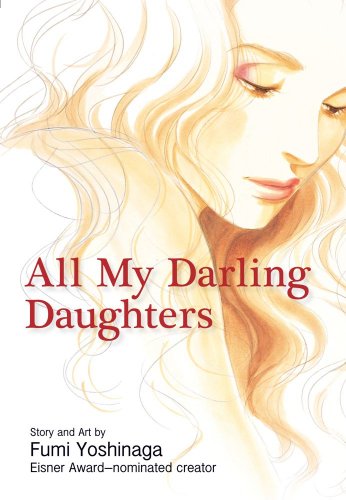

All My Darling Daughters

All My Darling Daughters

By Fumi Yoshinaga

Rated T+, for Older Teen

Viz, $12.99

The centerpiece of All My Darling Daughters is a two-part story about Sayako, a woman who decides to have an arranged marriage. We look over her shoulder as she goes to dinner with a businessman who denounces those who don’t pull their own weight, a doctor who thinks women should be “natural and feminine,” not aggressive and short-haired, and a sweaty salaryman who immediately propositions her. Finally, she meets a man who is physically damaged but beautiful inside, and you think, ah, here we go.

But this is not a Harlequin romance. Instead of following the standard script, Sayako takes things into her own hands, and the resulting twist is both surprising and satisfying.

All My Darling Daughters is a self-contained set of five short stories about families and relationships, and each one takes a dip into unexpected territory. The framing tale is that of Mari, a working single mom, and her daughter Yukiko. The book begins with Mari’s abrupt announcement, following a bout of cancer at age fifty, that she has gotten married and her new husband, Ken, will be moving in with them. Yukiko is unnerved to learn that her new stepfather is younger than her, and at first their relationship follows a predictable, spiky curve. What makes this story so great is that Yoshinaga shows, rather than tells, what is going on; watching Mari and Ken prepare dinner together, Yukiko realizes that everything has changed. She moves in with her boyfriend, but she visits frequently, and much of the rest of the book unfolds as the family sits around at dinner, telling stories and arguing, as families do.

Like all real families, Yukiko’s family is messy and ambiguous. There are nice people and people who are not so nice, one heroically good character but no clear-cut villains. One of the threads that runs through the story is Mari’s insecurity about her looks, which she blames on the way her mother used to speak to her as a child. But in the final story, we see her mother’s point of view, and we learn that her negative comments were well intentioned. Another story, about a mediocre college professor and his sexually aggressive student, flips the usual norms of manga romance on their head.

Although the characters sleep on futons and eat with chopsticks, the situations and conversations in this book are universal. In fact, I felt like Yoshinaga was channeling me in the very first scene, when Mari returns home from work and scolds Yukiko (a teenager at the time) for not cleaning up or at least making tea. If she had added “Couldn’t you at least empty the dishwasher?” I would have started looking for hidden cameras. The story does get a bit more baroque after that, but Yoshinaga always allows her characters to find happiness in a number of ways, conventional or not, and somehow it all works out. It’s very refreshing.

This is the difference between truly mature manga and genre-bound shoujo or shonen. So much manga reflects our worst stereotype of Japan, the rigidly dictated roles, the all-or-nothing society in which anyone who doesn’t conform is bullied into suicide or seclusion. The bad suitors in the arranged-marriage story exemplify those stereotypes, but the woman, Sayako, rejects them all and makes her own path. While Japanese life often seems sterile in fiction, here it is rich with humor, anecdote, and ambiguity.

Yoshinaga’s art has grown in precision and complexity since her earlier works, such as Antique Bakery. There, she had a trick of placing a single head in a large panel with only blank space surrounding it. What could be a cheat in a lesser artist’s hands seemed monumental when she did it, but it could get monotonous after a while. In All My Darling Daughters she crowds the pages with more panels and more detail, which may be less pure but is also more interesting. She still uses the big, empty panels, but she saves them for major announcements, and they punctuate the flow of the story rather than dominate it. Yoshinaga’s clean linework is easy to read, and the pages never look cluttered. Her women are precisely drawn, and each one has a personality that shines through from their first appearance on the page. They all have a familiar look, too as if they were someone you knew once.

In terms of production quality, Viz has put together a beautiful package, with a gorgeous cover and cream-colored paper that really shows off the art without fatiguing the eye. Even more than most of the titles in the Signature line, this book feels deluxe, like a graphic novel for adults; it’s as far as you can get from Naruto.

Not that All My Darling Daughters would ever pass for anything other than manga. The storytelling style and the stories themselves all echo familiar manga tropes, but in Yoshinaga’s hands they have grown up and become something rich and strange—and highly entertaining.